Undoubtedly, wine is among nature’s choicest gifts; the grape’s leap toward immortality. But the best part about wines is that it’s the oldest natural beverage that solicits practically no human intervention. The grape vine is an ivy plant, much like the omnipresent money plant. Just like growing a money plant needs little more than a leaf left in water, sans soil, nutrients, fertilisers or even sun; grapevines flourish almost as independently. The fruit brings natural sweetness, the yeast in the air feeds on it, and voila, you have wine. Since wines weren’t an invention as much as a discovery, it’s only fitting that we, as consumers, would attempt to create better wines. Ironically, winemakers are now designing wineries, equipment, and processes in tune with natural elements to advance nature’s largesse.

LET GRAVTY BE

Wineries, much like other buildings have long been constructed over the ground. However, an increasing number of winemakers today are aligning with the principles of gravity to create underground wineries for a plethora of reasons. This stems from the simple idea that winemaking is mostly a vertical process. So while the land you deploy to create a winery might be limited, there is no end to how deep one can go.

Pernod Ricard’s star winery Campo Viejo in Rioja, Spain, is built inside a natural hill that has been hollowed to home a winery inside. From the outside it may look like a natural feature in continuation of the scenic landscape, but inside its belly runs a meticulous operation, quite like Dr. Evil’s lair in the movie Austin Powers. Grapes are sourced from the vineyards, taxied to the top of the hill, and carefully dropped into the pneumatic presses. The nectar is pressed out, which continues to flow into the chambers below with fermentation tanks lined up with absolute precision. After fermentation is over, these finished wines are moved to the level below where an ocean of oak barrels await. Once these wines are rested enough to reach their desired age statement—Crianza, Reserva, or Gran Reserva—they descend to the floor below where they are bottled and shipped out. All aligned with nature’s free will and flowing with gravity.

Similarly, the Charosa Vineyards in Nashik in India, the winery was constructed on the principals of gravity from its inception. This natural force ensures these fragile berries are only hustled as much as nature desires them to be. The gentle movement, as opposed to pumping, also ensures that the juices and finished wines face no friction. Whenever pumped aggressively or with pressure, liquids create bubbles. These are nothing but oxygen, which is wines’ biggest enemy, turning them to vinegar.

GOING BELLY UP

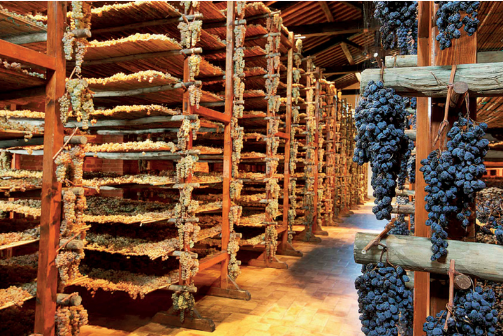

Underground wineries also allow other benefits such as the restricted infiltration of light. Wines rest like us human beings. Just like darkness ensures a good night’s rest, so also light causes wines to alter their colour, and can cause alterations in their acidity, tannins, and flavours. Light also causes heat and pressure, causing stress to the liquid, often leaving a tired flavour profile. More so since wines are usually aged for extended durations before they are released. In case of Barolos and Champagnes, wines stay in these cellars from a couple of years to up to a decade, for Brunello di Montalcinos it could even be a decade and half or more. Hence, sleeping at peace almost becomes imperative. These underground caves also compress vibrations from the movements above and provide consistent cool temperatures throughout the year.

NATURE MEETS TECHNOLOGY

Even before glass bottles were introduced in the 1780s, steel’s promotion had been cemented during the post-industrial revolution, but winemakers preferred with oak and concrete. While oak is still an unmissable feature in wineries, concrete lost its sheen. It couldn’t be moved easily, the size couldn’t be negotiated, cleaning was a mess, and there was barely any temperature control possible in these mini room-sized fixtures. However, concrete has made a comeback to become the Yeezys and the Nike Airs of wineries now, with contributions from technology, of course. Since it makes most sense to toy with natural elements at a winery, amphoras and concrete tanks are back in vogue and Grover Zampa Vineyards are championing this drive, especially now with their uber-prestigeous Signet collection. Greeks and the Armenians, the oldest winemakers, used to ferment, store, and ship wines around in Amphorae (matka). Their clay is a tad coarse for a newly-made wine, however, eventually turns in to a soothing nurturer. The tannin integration gets cosier, fruit extraction gets brighter, and delivers a mouthfeel and structure unparalleled to that from stainless steel or bottlerested wine. Concrete eggs are also increasingly stealing space in fermentation halls. Shaped like an actual egg- -inverted or not—they provide a rotation and constant movement to the liquid inside, keeping it at work even while it’s resting, extracting the most out of the produce. The skins and solid liquid remain suspended throughout rather than as a bed of solids or a cake floating up top.

SUSTAINABILITY

Superlative wines are not only a result of what happens within the winery, but what transpires outside and around it as well. A winery’s design isn’t confined to its physical structure; it is soulless without its operations and thought-fuelled design. Wineries are industrial setups that constantly guzzles resources; if they only take from nature, the relationship will be short lived. After all, it is nature that maketh the wine!

The country’s biggest winemaker, Sula Vineyards, is pioneering a project that works in tune with nature, turning the carbon cycle backwards. They’ve also championed wine tourism in the country, quickly becoming among the most sustainable winery in the world! From minimising their dependency on coal-fuelled power grid to making their own solar energy, reprocessing all water being used at the winery, to using battery operated mobile vehicles, and employing organic farm to table produce on site, to planting over 10,000 trees each year, Sula ensures that the ecosystem that delivers commendable quality produce also marches in step with nature. As they say, societies thrive when a generation plants trees knowing they’ll never enjoy its fruit and shade.